Insidious Swelling in the Neck of a 45-Year-Old Man

Background

Figure 1. (Click to enlarge) |  Figure 2. (Click to enlarge) |

A 45-year-old man presents to his primary care physician (PCP) complaining of gradual swelling in his anterior neck over the past 6 months. At first, he thought nothing of the swelling, expecting it go away on its own; however, over the past 2 months, it has become more noticeable. The patient has become concerned that the swelling may be caused by cancer. He has not experienced any pain in the area of the swelling, nor has he experienced fevers. Additionally, he denies any difficulty in swallowing and any alteration of his voice. There are no problems with his breathing. The patient has no history of trauma, and he denies any significant personal medical history. The family history is unremarkable. He is not currently taking any medications, he does not smoke, and he does not use any illicit substances. He is a social drinker.

On physical examination, the patient is afebrile and has a pulse of 72 bpm, a blood pressure of 130/82 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 12 breaths/min, and a normal oxygen saturation while breathing room air. He is well-developed and well-appearing. Examination of the anterior neck reveals a nontender, nonerythematous, fluctuant mass measuring approximately 10 × 8 cm in the midline of the lower neck, with slight extension to the right side of the midline. The mass moves up and down when the patient swallows, and it slightly displaces anteriorly with protrusion of the tongue. No cervical lymphadenopathy is appreciated. The lung fields are clear bilaterally, without any evidence of stridor or wheeze. The heart has a regular rate and rhythm, without murmurs, and the abdomen is soft and nontender, without evidence of masses. The cranial nerves are intact, and the remainder of the neurologic exam is unrevealing as well.

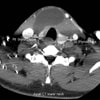

Some routine laboratory blood tests, which include a complete blood cell (CBC) count and an electrolyte panel, are sent, as well as a rapid assay for thyroid function tests. All of the laboratory investigations, including the thyroid studies, are within normal limits. An ultrasound of the neck is obtained (Figure 1). As a follow-up, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck is also performed for further evaluation (Figure 2).

Discussion

Figure 1. (Click to enlarge) |  Figure 2. (Click to enlarge) |

The ultrasound image in Figure 1 shows a large cystic mass anterior to the thyroid gland (arrowheads). The contrast-enhanced CT scan (Figure 2) demonstrates that same predominantly midline cystic mass extending anteriorly to the thyroid gland and under the strap muscles, without any evidence of ectopic thyroid tissue. The findings are consistent with the diagnosis of a thyroglossal duct cyst. This diagnosis is the most common etiology for a midline neck mass. Thyroglossal duct cysts usually occur between the hyoid bone and the thyroid gland, and they represent up to 70% of congenital neck anomalies. Thyroglossal duct cysts are second only to lymphadenopathy as the most common cause of a neck mass.[4,5]

The cysts usually appear in the midline and can be present anywhere along the line of fetal descent from the foramen cecum to the level of the thyroid gland. From an embryologic perspective, the thyroid gland develops during the third week of life as an outgrowth of the floor of the primitive pharynx. The primitive thyroid then descends from the foramen cecum to its mature position in the anterior neck through the thyroglossal duct. The thyroglossal duct is normally resorbed by 7 to 10 weeks of fetal life. Abnormal persistence of the thyroglossal tract accompanied by mucus production from the endothelial lining of the tract leads to the development of a thyroglossal duct cyst. Approximately 7% of the population has thyroglossal duct remnants, and the distribution is equal among males and females. The cysts are usually found in children or adults younger than age 30 years, but they can develop in adults of any age. In recent years, a number of older patients, including patients in their 80s and 90s, have presented with thyroglossal duct cysts. There are 4 general types of thyroglossal duct cysts: thyrohyoid (61% of cases), suprahyoid (24%), suprasternal (13%), and intralingual (2%).[2,3,4,5]

The differential diagnosis for neck masses can be categorized by the location of the mass itself; the usual categorization is between lateral and midline masses. The most frequent causes of lateral masses are lymphadenopathy, branchial cleft cyst malignancy, cystic lymphangioma, and dermoid and teratoid cysts. Although thyroglossal duct cysts are the most common etiology for midline masses, the differential diagnosis also includes dermoid and teratoid cysts, ectopic thyroid tissue, malignancy, and cystic lymphangiomas.[4]

On radiologic images, thyroglossal duct cysts appear as a cystlike mass along the course of the thyroglossal duct. They must be differentiated from dermoid cysts and lymphangiomas. A dermoid cyst usually contains fat; lymphangioma is most common in infancy or early childhood, and it usually occurs in the posterior triangle of the neck, behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle. A thyroglossal duct cyst must also be differentiated from an ectopic thyroid gland. If an ectopic thyroid gland is mistakenly removed, the patient may require long-term thyroid treatment for hypothyroidism. Often, patients with an ectopic thyroid also have hypothyroidism, and they will have an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level.[4]

The diagnosis of thyroglossal duct cyst is made on the basis of the clinical history and confirmed with diagnostic imaging. Most patients with thyroglossal duct cysts present with either a history of a slowly growing, asymptomatic mass or of a relatively rapid-growing mass (if the cyst is infected) in the anterior midline of the neck. Frequently, the swelling is exacerbated during an upper respiratory infection. The pathognomonic sign of a thyroglossal duct cyst is that it moves with swallowing and with protrusion of the tongue; however, the mobility of larger cysts may be restricted. Imaging studies, including ultrasonography and CT scanning of the neck, will confirm the diagnosis and help to rule out the presence of a possible ectopic thyroid gland. Thyroid function tests should be obtained to confirm normal thyroid function.[3]

Once diagnosed, thyroglossal duct cysts are removed because they are cosmetically undesirable and have the potential to become infected and undergo malignant transformation. The treatment of choice is the Sistrunk procedure, named after Dr. Walter Ellis Sistrunk and first described in an article in 1920. The procedure, rather than involving a simple excision of the cyst, involves dissecting the central portion of the hyoid bone, with extension of the excision up to the base of the tongue to include excision of a small block of muscle around the foramen cecum. Because of the increased risk of thyroglossal duct carcinoma, some practitioners further recommend the addition of thyroid suppression therapy or a complete thyroidectomy; however, this practice remains controversial. The recurrence rate associated with simple excision of a thyroglossal duct cyst is approximately 50%, whereas the recurrence rate associated with a formal Sistrunk procedure is approximately 5%. The rate of recurrence after a Sistrunk procedure is increased, however, when a thyroglossal duct is ruptured during dissection. A history of previous infection of the cyst, previous incision and drainage procedures, and adherence of the cyst to the skin all increase the risk of rupture during dissection. If the cyst is infected at the time of diagnosis, treatment with antibiotics, such as ampicillin/sulbactam, amoxicillin/clavulanate, or clindamycin, is indicated before surgical excision.[2,4,5,6]

The most common complications of thyroglossal duct cysts are infection with the possibility for abscess formation, spontaneous rupture, and formation of a secondary sinus tract. A Sistrunk procedure mistakenly performed for thyroid ectopia that removes thyroid tissue can cause hypothyroidism. The cysts can compress the trachea and lead to respiratory distress, especially if they are rapidly expanding (although this is not common). Carcinoma is the most feared complication, occurring in about 1% of all cases, with papillary carcinoma accounting for 85-92% of malignancies and follicular carcinoma accounting for the rest. Most patients who develop carcinoma tend to present at a later age. Cancer in a thyroglossal duct cyst seems to be more common in females than in males. The diagnosis of carcinoma arising in a thyroglossal duct cyst is typically made postoperatively by histology.[4,5]

Because the patient in our case presented with a thyroglossal duct cyst which (on clinical grounds) was not infected, he was not given antibiotics. The ultrasound study confirmed the presence of a thyroglossal duct cyst and ruled out the possibility of an ectopic thyroid gland. The patient underwent an elective Sistrunk procedure, with no rupture during dissection. There were no complications. He was discharged from the hospital the following day. Postoperative histologic analysis did not reveal any evidence of malignancy. On follow-up in the clinic 2 weeks later, the patient was noted to be doing well.

No comments:

Post a Comment